Friday essay: finding spaces for love

Friday essay: finding spaces for love

Ideas about love changed a great deal over the centuries before modernity. Romantic love and a primary focus on intense, individual feelings and personal bonds were literary conceits more than socially legitimised reality, especially when arranged marriages were the norm at the elite level. There was a gap between the places where love was shaped and performed visually, and the venues in which it was validated socially.

Wooing was conducted at masquerades and balls, but also in churches and markets, and sex was obtained at inns and bathhouses as well as in brothels and alleyways, but not all of these locations were eroticised in images.

Weddings were festive yet decorous events on the whole, as shown by Jan Steen in The wedding party (c. 1667–68), in which the demure bride waits in the background while others raucously dance near her nuptial bed, enacting a fervour she could not show.

Love was visually represented in conventional, familiar terms, reiterating and expanding the stories from courtly love poetry and classical mythology.

Gardens of love and pastoral settings

Late medieval and Renaissance art often pictured love set within lush, secluded gardens, its inhabitants enjoying perfect weather, charming music, abundant flowers and amorous flirtation. Separation from the everyday world is a key theme, as is emphasising unending, leisurely pleasure. The dream partly derives from the ancient idea of a Golden Age of timeless harmony, peace and prosperity set in ever-fruitful fields. Arcadia is a related fantasy stemming from ancient literature, a poetic region of tranquil wilderness inhabited by pastoral shepherds and nymphs, domain of the rustic god Pan.

Judeo-Christian culture also locates the earliest beginnings in a paradise, the Garden of Eden. That monotheistic age of initially idyllic, peaceful and ageless perfection is distinctive, however, for having a solitary, named pair of human residents. Eve was created to be Adam’s reproductive companion, and only after eating the fruit of the tree of good and evil did they come to know desire, shame, toil and mortality.

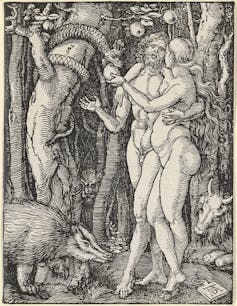

Albrecht Dürer’s series of 37 woodcuts known as The Small Passion (1511) begins with a depiction of the temptation of Adam and Eve known as The Fall of Man, heralding the commencement of human history and the need for redemption from sin. As Eve takes the apple and Adam opens his palm to accept it, one side of his face in shadow, these “first parents” are already shown in physical intimacy, arms wrapped around each other as a foretaste of their sexual future. Rather than standing in a garden of pleasure, they are in a thick, dark forest, a foreboding sign of their sin.

German artists such as Dürer often focused on the dark side of passion, contrasting young lovers with skeletal death as a way of reminding viewers to live without the sins of lust and excess because judgement awaited in the afterlife.

Dürer’s engraving of a Young couple threatened by Death, also known as The promenade, has Death lurking behind a tree, holding an hourglass that shows the sands of time running down, while in the foreground a gallant, feather-capped youth invites a stylish lady to accompany him on a stroll.

She stands in demure profile, her dress gathered at her womb area and her hands folded sedately in front, in a fashionable pose that, like her low neckline, emphasises her shapeliness and femininity as well as potential fertility. He too is fashionably dressed, his codpiece and hose accentuating a lean body, the long sword rising up between his legs suggesting that he is barely keeping himself in check. The courting couple stand on a high rise overlooking a river and distant town, alone at the edge of human settlement, private but also on the cusp of deciding whether to be civilised and constrained or take advantage of the isolation and indulge their appetites.

Marginality instead provides only the opportunity for sex in the case of an earlier engraving by Dürer, The ill-assorted couple (c. 1495). Once more tackling a popular topic in northern Europe – age disparity between sexual partners – Dürer pictures a couple in terms of lust and greed.

Bearded and balding, the man rummages in his purse for a coin to place in the outstretched hand of the woman whose own purse is open. The transfer not only signals prostitution but also indicates more literally sexual union. The sinners rendezvous near a lake and a town but their grassy spot is relatively barren, promising none of the pleasures of garden or panorama.

Isolation on the edges of human habitation was not the only pictorial convention, however, for the alternative tradition of groups in an enclosed garden proved highly attractive. Allegorised passion outweighed moralising about lust in images that were visually charming as well as biblically sanctioned.

Parallels were drawn between the bride of the Song of Songs in the Old Testament and the mother of Christ in the New Testament, the Virgin Mary. As this bride, she was allegorically cast as the Catholic Church in mystical union with Christ, and her virginal purity was signified by the secluded garden, closed off from all sin.

The Bible’s passionate celebration of the bride as a “garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up” informed the poetic and pious tradition of walled gardens, including the actual cloisters of nuns and monks as well as religious imagery.

However, intimacy, relaxation and potential sensuality were seen in secular gardens and images too, ornamenting domestic residences with refreshing views of greenery and enjoyable depictions of amorous pursuits. Gardens, often with fountains, were especially popular settings for courtly love as rendered on French and Italian ivory combs, caskets, coffers, wedding chests and birth trays, and in prints and manuscripts.

On occasion, a room’s upper walls were decorated with foliage, sometimes populated with figures from romance literature, as can still be seen in the Palazzo Davanzati, Florence. A rare surviving example of a large panel is The Garden of Love (c. 1465–70), which once adorned the high walls of an unknown palatial interior in northern Italy. Figures stand either side of a large marble fountain, enclosed within a tall trellis of what were originally crimson and white roses.

Within their secluded, fragrant enclosure, the courtly young people play games. On the right, a smiling woman is about to blindfold her male companion. On the left, another woman concentrates on filling her syringe with water from the fountain, an action the man already cannot see because his raised hat blocks his view. The syringe is a fascinating detail, resembling a smaller version of hand-held fire extinguishers made of brass and wood and medical instruments used for clysters (enemas). As with usage of the latter, sexual double entendre about the ejection of fluid endows The Garden of Love with an erotic undercurrent.

Two onlookers at the far left await the action, the man looking out and gesturing to ensure that viewers too stay attentive. What will happen at any moment is that the blindfolded man will be squirted with water from the syringe.

Water games exploiting the element of surprise were popular in elite circles; for instance, unsuspecting guests strolling in a garden might suddenly find themselves in the midst of spray from hidden sprinklers. The audience of this panel is thus involved in amusing anticipation, cooled by verdant foliage, gleaming marble and trickling water, and thrilled by awareness of impending trickery and laughter.

Despite or, rather, because of increasing urbanisation, nostalgia for imaginary gardens and Arcadian peace continued to fuel depictions of amorous encounters and allegories. Botticelli’s Primavera, (c. 1475–82), is one famous example. However, as indicated by Botticelli’s focus on classical figures like Flora, Cupid and the Three Graces, avant-garde art was increasingly turning from courtly love to mythological stories for its characters, plots and fantasies, and to pastoral settings for its poetic dreams.

For example, in the mid-16th century, Titian’s Venus reclines while listening to organ music near a window that looks out on a garden with an avenue of trees, a promenading couple and a large satyr-fountain. Flowing, splashing water glistens in the sunlight and enhances the sense of lively action.

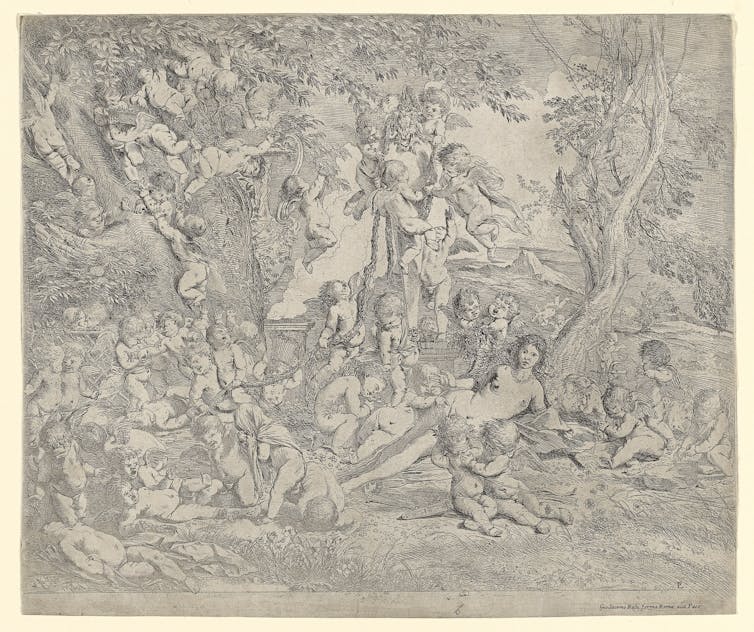

A more playful mood imbues the realm of Venus, goddess of desire, in Pietro Testa’s etching, where she luxuriates in her garden filled with busy putti who gather fruits, sharpen the arrows of love, festoon statuary, fight, cry and play peekaboo. The absence of a particular narrative here adds to the sense of liberation and timelessness. Similarly, no story anchors the shepherds and rustic characters populating pastoral sites, which were increasingly common in the 16th century.

At other times, new stories were told, epic quests set in strange lands and faraway places. The ancient world of mythological characters and physical ruins inspired the inventive romance The Dream of Poliphilus, printed in Venice in 1499 with numerous woodcuts. Poliphilo dreams his way through landscapes and gardens to be united eventually with his love Polia at the Fountain of Venus in a classicised version of courtly love tales such as the medieval Roman de la Rose.

Torquato Tasso’s long poem Jerusalem Delivered (first printed in 1581) instead reimagines the first crusade, combining heroic ventures with conflicts about love. At one point, the great knight Rinaldo is distracted from his mission when he falls in love with the seductive witch Armida, and his two companions Carlo and Ubaldo must rescue him.

In her garden, they encounter a charming fountain, where siren-like bathing nymphs unsuccessfully try to lure them from their task with tempting food and rest, but they have been forewarned about the peril of the Fountain of Laughter, the waters of which make one laugh so much that they die.

Unlike Adam, their masculine exercise of reason and valour overcomes these feminine enticements, a victory celebrated in tapestries designed by Simon Vouet and first woven in the 1630s, one version of which – Carlo and Ubaldo at the Fountain of Laughter, 1640–50 – is owned by the NGV.

While sensual pleasure is more usually celebrated in the visual arts, some examples warned of its emasculating dangers. In Tasso’s case, Europeans were feeling threatened by the Ottoman Empire, based in what is now Turkey, and the Catholic Church was undergoing moralising reform. Notably, in Vouet’s illustration of Tasso’s text, the foremost nymph modestly cloaks her genitals and those of the other figure are ostensibly masked by water. The fountain demurely dispenses water from a fictional vase and dolphin as well as from the mouths of nasty satyrs, whereas Poliphilo was splashed in the face by water that seemed to come from the organ of a pissing putto.

Laughter, or at least charming smiles, returned in art produced for the indulgent aristocrats of 18th-century France before the upheaval of the Revolution in 1789. Happy peasants and mythological deities relax in delightful countryside, presenting idylls of satisfied rustics, or indolent youths of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy enjoying the countryside in pictures ornamenting a French fan.

Antoine Watteau and his circle produced fêtes galantes, paintings of bucolic ease and amorous play tinged with theatrical masquerade, including a variant after the lost original, Jealousy (c. 1715). François Boucher was adept at pastoral sensuality, cunningly captured in the pair of oval canvases, The mysterious basket and The enjoyable lesson of 1748.

The action appears obvious enough: flowers with a sealed note stealthily delivered by a shepherd on behalf of a suitor in one, a music lesson enabling subtle closeness in the other, each set against the backdrop of overgrown forest and monumental ruins.

Yet sensual undercurrents counter the paintings’ aura of innocuous tact. In the latter painting the musically adept shepherd fingers one kind of rod at the damsel’s lips while she handles another that juts out from his groin. Viewers are put in states of anticipation and self-assurance about inside knowledge regarding the place of love and desire in Arcadia.

Gardens and isolated, outdoor nooks are visually presented as spaces for romantic play, alluring temptation and untrammelled lust, investing in either nostalgia for lost perfection or cynicism about innately bestial humanity, though often the art alludes to both. To dismiss the imagery as mere escapism or straightforward moralising is too easy an assessment.

Social factors such as increasing urbanisation and shifts in agricultural production and modes of leisure as well as increasing literacy regarding antiquity, alongside familiarity with contemporary poetry, all help ground the imagery in its context.

Music, poetry and the visual arts shaped and explored ways of thinking about various emotional states like yearning, pleasure, love and disappointment. Artists produced conventional yet meaningful, vivid imagery that was assuring and arousing, licensing desire, inviting playful relaxation and generating conversation.

Bathhouses and taverns

The imaginary scenario of bathing in peaceful glades or hidden pools enabled the depiction of naked bodies in a variety of poses, but actual establishments used for hygienic or curative purposes were often associated with licentious behaviour. Like taverns, they offered food and drink, and sometimes functioned as brothels too. Venereal mingling of men and women at the spa of Baden in Switzerland attracted particular comment, described in 1611 as

a second Paradise, the seate of the Graces, the bosome of Love, and the Theater of pleasure.

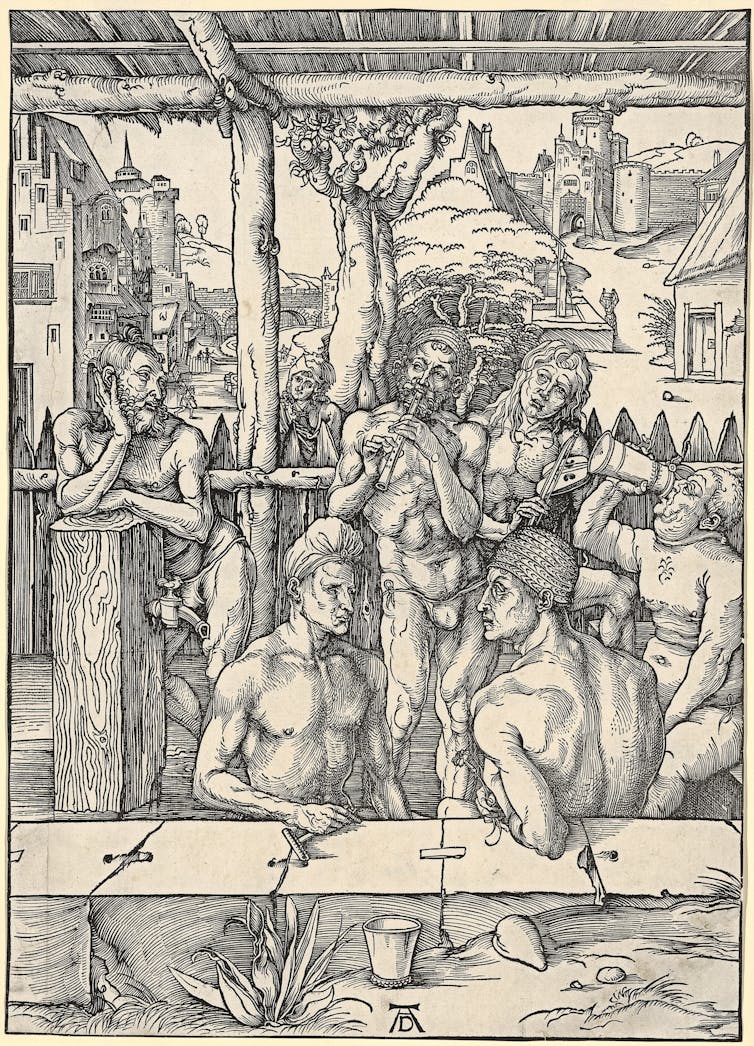

That visual tradition is imagined anew in Dürer’s strikingly large, fresh woodcut of a men’s bath in The bath house, thought to be designed around 1496–97. Six almost fully naked men are enclosed within a roofed structure that is open on all sides, looking out on vistas of both townscape and countryside, and enabling one clothed youth to gaze at the scene from the rear palisade.

Visual jokes add to the pleasure: the tree behind the onlooker resembles a fully naked figure with upraised arms, and the tap at the left is not only a cock or valve in German (Hahn) but has a spigot in the shape of such a bird, each reminding viewers of a slang term for the male genitals situated behind the tap.

The sexual tenor might at first appear to be moderated by the absence of women, but the all-male grouping is subtly homoerotic, especially conveyed by the interchange of gazes. The two figures in the foreground look fondly at each other, one holding a scraper that he could soon use on his companion’s back, the other holding a flower, which usually indicates courtship.

Dürer’s presentation of amiable homosociability and male eroticism suits the humour and innuendo that circulated among his own friends. The context of a bathhouse is nostalgic, however, for that communal institution was closed in his home town of Nuremberg in 1496 due to concerns about the rising epidemic of syphilis, a public health problem that eventually led to the demise of bathhouses throughout Europe.

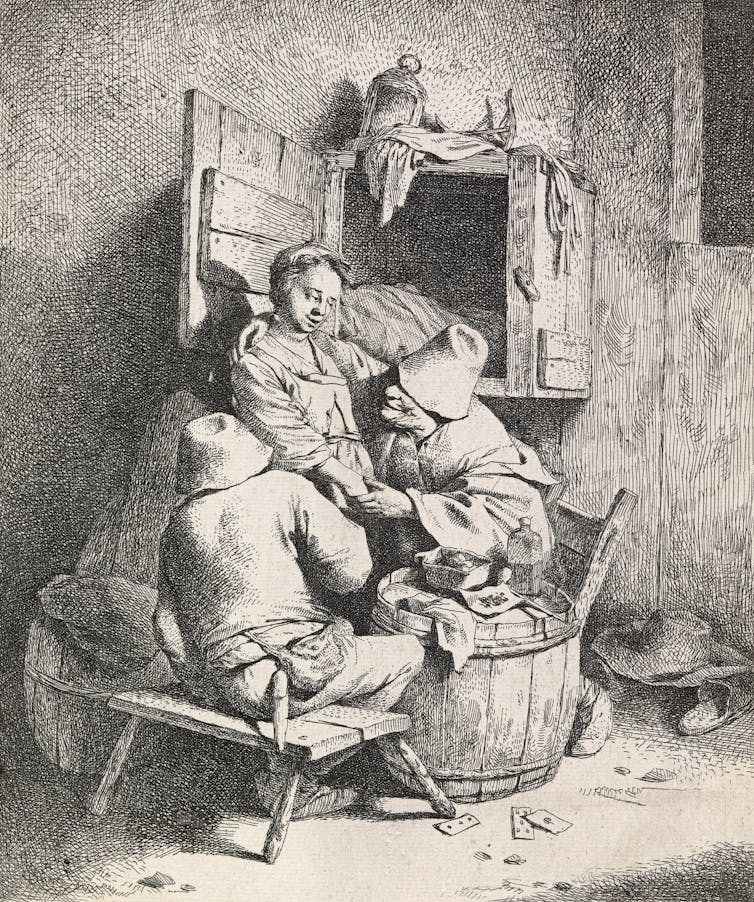

Taverns, rather, continued to be sites of public sociability and communal sensuality, often doubling as brothels. They were a popular subject for 17th-century Dutch artists such as Cornelis Bega, whose etchings represent peasant men fondling women who worked as both waitresses and prostitutes. The bedding in a small cubicle behind a woman being propositioned points to her future activity with the eager male client.

Scattered cards on the ground indicate the common pastime of gambling and the half-empty bottle on the barrel table affirms the man’s intoxicated state. A long-stemmed pipe, tobacco – imported since the late 16th century from the New World by Dutch merchants – and a pot of embers for lighting the pipe demonstrate his indulgence in the popular habit of smoking, which was at the time referred to as “drinking” a pipe of tobacco.

Raucous behaviour in taverns was often an amusing topic for the painter Jan Steen, who came from a family of brewers and for a while in the 1670s ran his own tavern in Leiden. His Interior from the first half of the 1660s has one smiling rake caress the swollen breasts of a nursing mother, unbeknown to the child’s probable father, a drunken man with loose leggings who tries to concentrate on manipulating tongs in order to pick up an ember with which to light his pipe.

Behind them, a group of men in the company of one woman gleefully and noisily enjoy gregarious companionship.

Interior romps

Amorous images set indoors were also exercises in powerful imagination rather than documentary exactitude. Moral decorum and practical circumstances such as chilly rooms, for instance, meant that couples were frequently not fully naked during sexual intercourse, though mythological deities like Mars and Venus usually appear so when in amorous embrace. Husband and wife might have separate bedrooms and that space was not the realm of private intimacy that we expect today.

But in visual culture the bed was the arena for sexual romps, featured in erotic prints like the infamous, banned series called I modi, (c. 1524), engraved by Giulio Romano and Marcantonio Raimondi.

Those men were members of the Raphael circle active in Rome and Agostino Veneziano (also known as Agostino dei Musi) was another. His engraved Venus and Vulcan surrounded by cupids, 1530, records a popular composition in Raphael’s circle, among other sites frescoed above a fireplace in Mantua.

Vulcan, blacksmith and god of fire, was a common subject for such sites and his forge is visible in the background. The workplace is pictured adjacent to the bedroom, symbolic place of fiery passion, yet Venus, wife of older, lame Vulcan, is engaged in domestic rather than personal passion, assisting cupids in their preparation of the weaponry of love that has been fashioned at Vulcan’s forge.

Venus’s sexual life concentrates on adultery with the martial god Mars, seen in the engraving designed by Bartholomeus Spranger and cut by Hendrick Goltzius in 1588. Aided by Cupid and putti, naked Mars and barely cloaked Venus embrace enthusiastically, his fondling left hand nearing her sexual centre. The weapons of both Mars and Cupid lie discarded on the floor of a palatial bedroom, furnished with a plush bed looking out on distant landscape.

The Latin inscription tells us that to the sun god Phoebus, visible in the sky, “nothing remains secret or concealed”, a theme that is not only about the nudity and discovered adultery but is also central to the artistic enterprise. Despite the inscription’s moralising tone, the revelation as the bed curtains are lifted makes of artist and viewer a Phoebus-like, all-knowing voyeur.

Seeing absolutely everything is too much in the case of Semele, who is featured on Nicola da Urbino’s maiolica plate of c. 1524. The mortal woman Semele was one of Jupiter’s many lovers but his jealous wife persuaded her that she needed to see the supreme god in all his uncovered glory.

The subsequent scene, as shown on the plate, is set in the god’s grand, spacious hall rather than a bedroom. His stark power was so great that she was incinerated by fire from his lightning bolt, a tale about masculine potency, misguided desire and the power of sight.

Artists’ workshops were often sexually charged settings, filled with apprentices whose homoerotic charms were extolled by Leonardo da Vinci. When, on rare occasions, artists resorted to actual female models, the women willing to pose were prostitutes or other marginalised workers and they ran the risk of being raped, as happened in the studio of the 16th-century sculptor Benvenuto Cellini.

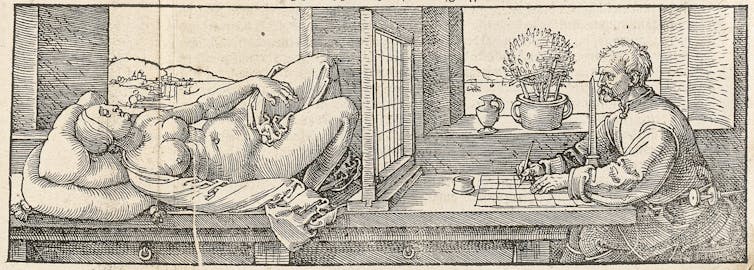

Dürer, once more, dared to picture the sexual dynamics. His treatise on artistic practice, printed posthumously in 1525, contained woodcuts that showed how to draw, with the aid of a see-through grid, convincing views of 3D objects like a lute, vase or female body.

A theoretical demonstration rather than a genre scene, Dürer feminises his subject and renders the artist as quintessentially male, powerful and voyeuristic. He begins the difficult task of perspectival foreshortening, in which the vanishing point penetrates the woman’s barely cloaked body.

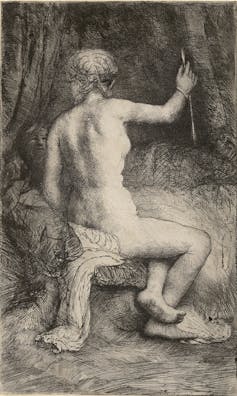

Rembrandt’s artist is instead barely visible in his etching of The woman with the arrow, 1661. His face emerges from the richly inked mid-ground at the left, looking up at a seated woman whose right arm is raised. She holds an arrow but the cord around her wrist and the position of the arm make it clear that the model’s actual, tiring pose was only made possible with the aid of a rope or sling.

The etching was perhaps initially a study for Venus holding aloft Cupid’s confiscated arrow, but Rembrandt nevertheless inserts the anonymous male admirer and pretends that viewers are able to enjoy a behind-the-scenes glimpse. Yet the print allows only a partial view of the woman, whose facelessness preserves her privacy.

Dürer’s workplace is measured and merciless, Rembrandt’s atmospheric and empathetic. Just as love and desire are complex, so too are representations of those overlapping states. Single images mingle innocent love with erotic undertones, as in the Venetian garden of love, Dürer’s bath house and Boucher’s pastoral idyll.

Death stalks one courting couple while others frolic at a fountain, serpents and sirens lurk in some gardens but at other times putti dance and play, shepherds and bathers enjoy music and Venus always takes her pleasure.

This is an edited version of an essay that appears in the catalogue for the exhibition Love: Art of Emotion 1400–1800, which opens at the National Gallery of Victoria today and runs until 18 June.![]()

Patricia Simons, Professor of Early Modern Art History, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: