From Peru to Colombia: the silenced voices of women fighters

From Peru to Colombia: the silenced voices of women fighters

Camille Boutron, Universidad de los AndesThe October 2 referendum in Colombia is the country’s chance to end more than 50 years of civil war between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, better known as FARC - some 30 to 40% of which are women.

Representatives of the Colombian government and the FARC have declared their commitment to include a gender perspective in the peace agreement, but the experiences of other female combatants throughout history show that women risk being left out of narratives of war.

So how will Colombia’s female fighters be accounted for in the ongoing peace process?

Women in war

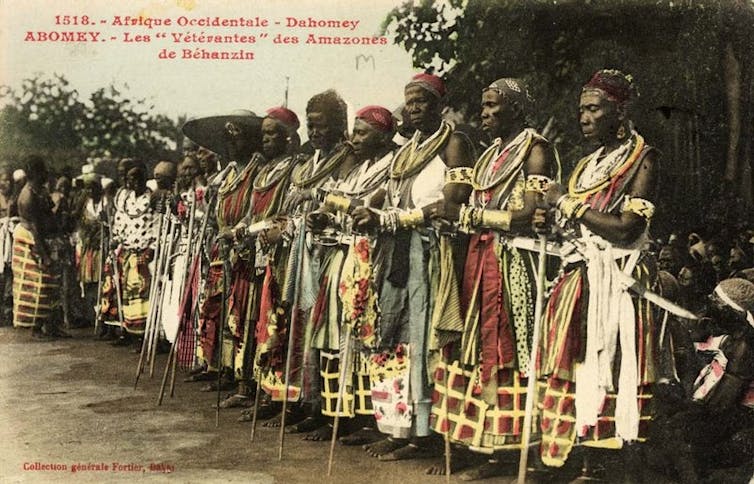

Women have always appeared on the battlefield – from the female fighters in the Dahomey Kingdom (modern-day Benin) in the 19th century, to the hundreds of thousands of Russian women soldiers who volunteered during the second world war, whose testimonies have been magnificently gathered by Nobel prize laureate, Svetlana Alexievitch.

As Alexievitch shows in her book, women’s contribution to war tends to be erased by history.

Women’s role in conflict has been traditionally associated with building peace, and the dynamic of male fighters versus women victims has historically dominated how we think about gender and war. Even today, the diversity and complexity of women’s war experiences is often silenced to conform with the frames imposed by international organisations, such as UN Women, which are the principal founders of peace-building projects.

It was striking to see, for instance, that the challenges faced by women ex-combatants were barely mentioned during the last summit of Women for Peace organised in Bogota.

The 2004 Abu Ghraib scandal, which disclosed the participation of female US soldiers in torturing Iraqis prisoners, showed that women are not by nature inherently more peaceful than men. From suicide bombers in radicalised groups to guerrilleras in revolutionary movements like Colombia’s, women have participated in one way or another every struggle in contemporary history.

The Shining Path

When I first started my doctoral research on women’s participation in the Peruvian armed conflict 11 years ago, my primary goal was to overthrow the idea that women are victims, not combatants. The Peruvian case was emblematic, notably because of the high level of participation of women in the Shining Path, a revolutionary Maoist movement that rebelled against the state in 1980. Some 69,000 people died in the conflict.

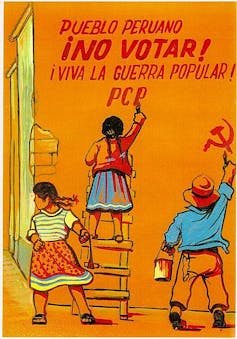

Like the FARC, women were thought to make up 40% of Shining Path militants, and also to occupy executive positions. The role of women in the movement was set out in a document called Marxism, Mariategui and the Women’s Movement, written by a group of female militants during the 1970s.

This document established the basis from which women’s issues would be treated within the Shining Path ideology. Several strategies were put in place in order to recruit female militants, peasants, students, and workers, and were coordinated by the Comité Femenino Popular (Popular Women’s Committee).

The Shining Path held an understandable attraction for young Peruvian women. During the 1970s, Peruvian society underwent several dramatic social changes, such as the democratisation of education and the emergence of the feminist movement, that considerably affected traditional social structures. Both occurred during a period of economic crisis and political instability.

The Shining Path provided an enticing alternative for young Peruvian women. Unlike other leftist parties such as Vanguardia Roja or el MIR that were reluctant to address feminist issues, Shining Path insisted on the central role of women in the revolution. The movement’s success in recruiting women, in other words, was mainly due to the failure of other political movements to understand that women’s issues were eminently political.

When Abimael Guzman, founder of the Shining Path, was arrested in September 1992, eight other militants were arrested with him. Four of these were women. Like female fighters who grab headlines today, the women got the most attention in the national press on the days following their capture.

Women militants of the Shining Path became objects of shame, and their representations in the press were used to discredit their leader - and indeed the whole party.

Writing women into the story

Women’s motivations for joining the armed struggle were diverse, as were their social origins, ages, and occupations. On the other side of the conflict, women contributed to the self-defense committees that were formed in the early 1980s to support the Peruvian army in the struggle.

Despite being mentioned by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in its 2003 final report, the contribution of peasant women to the war still remains neglected in histories of the conflict.

The physical and symbolic injuries caused by the armed conflict are tangible in Peru today. Thousands of men and women were incarcerated, mostly during the 1990s, some of them facing life sentences. Mass incarceration, then as now, had a particular effect on women and on their families.

It also raised new issues for reconciliation. For a peace process to be successful, the diversity of experiences that women had as combatants must be considered.

Colombia’s next phase

As I now begin a new research project in Colombia, I wonder how the question of women’s participation to that armed conflict is going to be treated by history.

I am working to understand how gender is understood in this specific context of war turning to peace, and it seems to me, for now, that women are still largely considered victims rather than political agents.

The Colombian peace process is different from that of Peru, mainly because Colombia is ending its conflict through negotiation. But there are lessons on inclusion to be learned. Women’s experiences as combatants must be visible in the post-conflict era. By escaping historical oblivion, women can find space for recognition and social action.![]()

Camille Boutron, Research assistant professor, Universidad de los Andes

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: