How a ‘feminist’ foreign policy would change the world

How a ‘feminist’ foreign policy would change the world

The Biden administration has a woman, Vice President Kamala Harris, in its second-highest position, and 61% of White House appointees are women.

Now, it has declared its intention to “protect and empower women around the world.”

Gender equity and a gender agenda are two ingredients of a “feminist foreign policy” – an international agenda that aims to dismantle the male-dominated systems of foreign aid, trade, defense, immigration and diplomacy that sideline women and other minority groups worldwide. A feminist foreign policy reenvisions a country’s national interests, moving them away from military security and global dominance to position equality as the basis of a healthy, peaceful world.

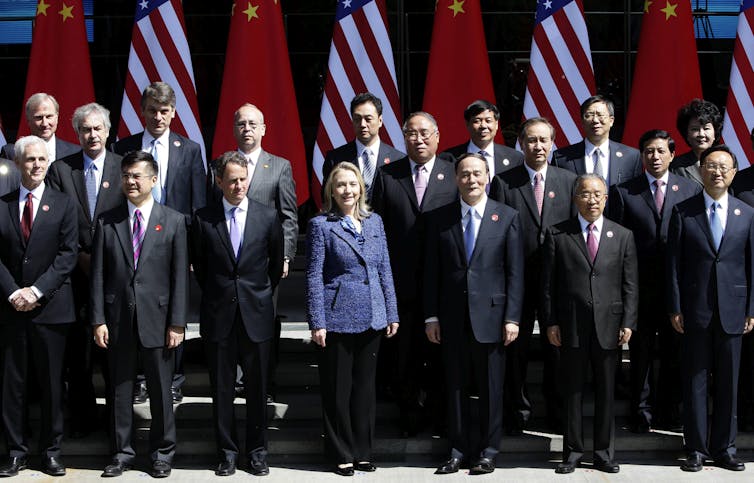

This is in keeping with Hillary Clinton’s groundbreaking 1995 statement at the United Nations, “Women’s rights are human rights.”

The world could change in some positive ways if more countries, especially a power like the United States, made a concerted effort to improve women’s rights abroad, our scholarship on gender and security suggests. Research shows that countries with more gender equality are less likely than other countries to experience civil war. Gender equality is also linked with good governance: Countries that exploit women are far more unstable.

Women aren’t yet any country’s top foreign policy priority. But ever more countries are starting to at least write them into the agenda.

Women at the bottom

In 2017, Canada launched a “feminist international assistance policy” aimed at supporting women, children and adolescent health worldwide.

Putting money behind its promises, it pledged Canadian $1.4 billion annually by 2023 to both governments and international organizations to strengthen access to nutrition, health services and education among women in the developing world. Some $700 million of this money will go to promoting sexual and reproductive health and rights and eradicating gender-based violence. Some $10 million over four years will go to UNICEF to reduce female genital mutilation.

In January 2020, Mexico became the first country in Latin America to adopt a feminist foreign policy. Its strategy seeks to advance gender equality internationally; combat gender violence worldwide; and confront inequalities in all social and environmental justice program areas.

Mexico must also increase its own foreign ministry’s staff to be at least 50% women by 2024, and ensure it is a workplace free of violence.

Neither Canada nor Mexico has achieved its lofty new goals.

Critics say Canada’s lack of focus on men and boys leaves the traditions and customs supporting gender inequality not fully addressed. And in Mexico, which has among the world’s highest rates of gender violence – men murder 11 women there every day – it’s hard to see how a government that cannot protect women at home can credibly promote feminism abroad.

But both countries are at least taking women’s needs explicitly into account.

Feminist foreign policy

The U.S., too, has taken steps toward a more feminist foreign policy.

In summer of 2020, under the Trump administration, the departments of Defense, State and Homeland Security, along with the U.S. Agency for International Development, each published a plan putting women’s empowerment in their agendas.

These documents – passed in accordance with a 2000 United Nations Security Council resolution on women, peace and security – promote women’s participation in decision-making in conflict zones, advance women’s rights and ensure their access to humanitarian assistance. They also include provisions encouraging American partners abroad to similarly encourage women’s participation in peace and security processes.

These are the components of a feminist foreign policy. But the plans are still operating in silos. A truly feminist foreign policy would be coherent across aid, trade, defense, diplomacy and immigration – and consistently prioritize equality for women.

One of Biden’s early moves in office, in January, was to rescind the “global gag rule,” a Republican policy prohibiting health providers in foreign countries that receive any U.S. aid from providing abortion-related services – even if they use their own money. Studies show the funding restriction reduces women’s access to all kinds of health care, exposing them to disease and forcing women to seek unsafe abortions.

Reallocating financial resources in ways that level the playing field for women is another critical aspect of a feminist foreign policy. But again, it needs to be a policy that’s consistent and across the board, not a one-off decision.

Afghanistan, women and peace

The U.S., long a leading world power, is unlikely to replace its international military security strategy with a purely “feminist” foreign policy.

But it doesn’t have to.

As the evidence grows that women’s well-being is central to everyone’s well-being, the connection between gender equality and global security can be naturally incorporated into updated global strategies focusing on traditional American goals like international security and human rights.

Afghanistan shows the necessity of – and opportunities for – a feminist U.S. foreign policy.

Afghan women were brutally discriminated against under the Taliban, with girls banned from education and women barred from leadership in politics, security and business. Now, under the Afghan government of President Ashraf Ghani, 28% of Afghan parliamentarians are women and 3.5 million girls are in school. Women worry that their freedoms could be compromised in any power-sharing agreement with the Taliban.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Yet American officials distinctly, and controversially, did not incorporate gender into negotiations with the Taliban militant group to end the war in Afghanistan. Only one U.S. negotiator is a woman – poor representation for a country that says it is committed to conserving Afghan women’s rights. The Taliban delegation has no women, and just four women sit on the Afghanistan government’s 21-member delegation.

With the United States’ help, an Afghanistan accord could secure the gains women have made since the United States toppled the Taliban in 2001 – or it could sacrifice them for “peace.”![]()

Rollie Lal, Associate Professor of International Affairs, George Washington University and Shirley Graham, Director, Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs and Associate Professor of Practice, Elliott School, George Washington University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: