Friday essay: toxic beauty, then and now

Friday essay: toxic beauty, then and now

Throughout history, humans have been willing to try almost any method or product to improve their physical appearance. In response, enterprising businesses and beauty moguls have conspired to sell us almost anything — from water to poison — in the guise of cosmetic treatments. While many cosmetic products have eventually proven to have little efficacy, a significant number have also caused physical harm and even death.

Cosmetics and cosmetic surgery are now subject to more stringent regulation than in the 19th century, when lead-based powders and face creams containing poisons were not uncommon. However, even today there are significant serious side-effects and potential dangers from cosmetic procedures, in particular.

For example, it was recently reported that cosmetic injections, such as platelet-rich plasma injections and facial fillers, are leading to a significant number of patients suffering from chronic, and potentially disfiguring, bacterial infections. While these kinds of non-invasive procedures are common, with over $1 billion spent annually on cosmetic jabs in Australia alone, research suggests that almost one-fifth of patients could suffer from such complications.

Of course, even when the greatest medical care is taken, there are still potential questions about the health risks of utilising Botox (Botulinum Toxin Type A) to combat or stave off facial wrinkles. While a large number of people, primarily women, have embraced Botox and believe it to be safe), in 2009 the US Food and Drug Administration added a warning noting that Botox “may spread from the area of injection to produce symptoms of botulism”, such as muscle weakness and breathing difficulty.

Further reading: Safety before profits: why cosmetic surgery is ripe for regulation

Even the most common beauty products still have potential risks associated with them. Consider lipstick, which is placed directly on the thin skin of the lips, readily ingested throughout wear, and reapplied multiple times throughout the day. Manufacturers are not required to list lead as an ingredient in lipsticks as it is regarded as a contaminant, but most contain lead, and some colours in much higher concentrations. An FDA test of 400 lipsticks conducted in 2011 found that every one contained lead. Nevertheless, the FDA advises that up to 10 parts per million of lead is an acceptable level.

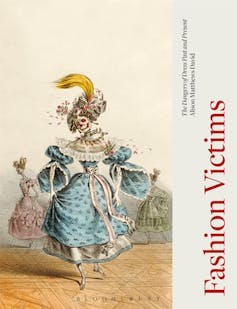

In her book Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present, Alison Matthews David explains that lead was a popular ingredient in cosmetics for centuries “because it made colours even and opaque and created a desirable ‘whiteness’ that bespoke both freedom from hard outdoor labour and racial purity”.

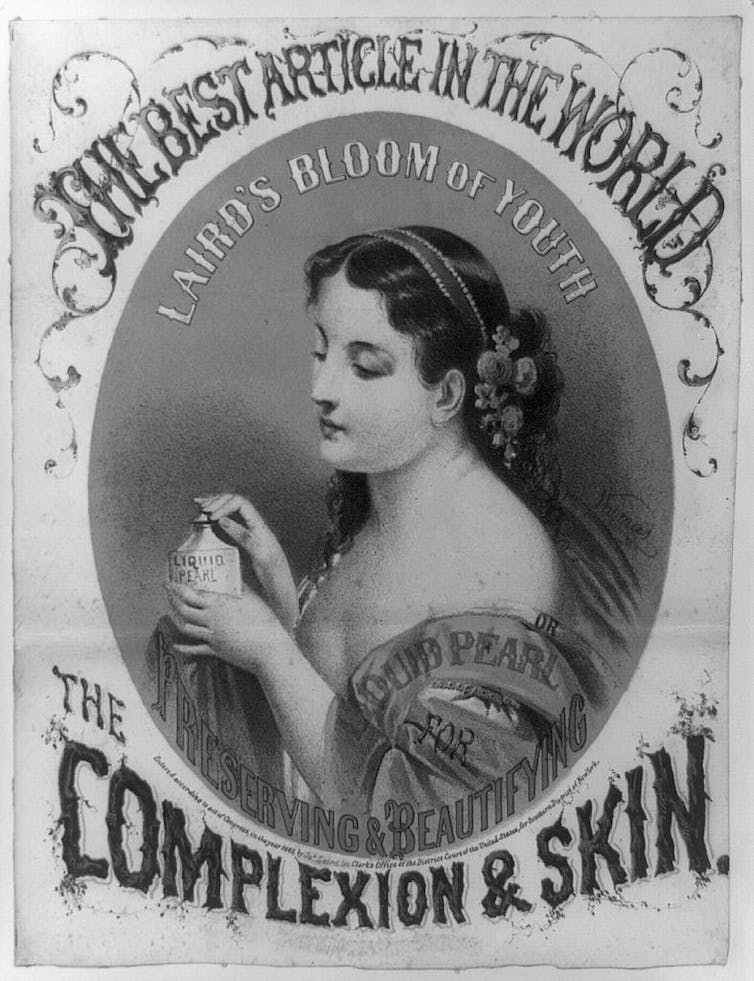

In the 1860s, the American face lotion Laird’s “Bloom of Youth or liquid pearl” promised to whiten skin, helping “ladies afflicted with tan, freckles, Rough or Discolored Skin”. The skin lightener, however, contained such a significant amount of lead that it caused “wrist drop”, or radial nerve palsy, in a number of women.

One woman’s hand had become “wasted to a skeleton”, while a St Louis housewife is recorded as dying of lead poisoning after extensive long-term usage of Laird’s and a home-made preparation containing “white flake and glycerine”.

In her book, Matthews David tells how she bought a vintage container of the American face powder “Tetlow’s Swan Down” that dates from the 1870s. It had been marketed as harmless and claimed to use whitening zinc oxide powder to replace once common toxic products such as lead, arsenic and bismuth. She had the powder tested with modern methods and found that it contained “a significant amount of lead”, which could be inhaled as dust during application.

Further reading: High amount of toxic metals in some cosmetics

A dark history

The serious regulation of patent medicines and cosmetics did not occur until the 20th century. This lack of government oversight meant that manufacturers could bottle and sell almost anything without having to verify their claims, subject their products to the rudimentary testing that was available, or clearly label the ingredients.

The key way in which American and British consumers made their decisions about products was based on the claims made and reputations built in extensive magazine advertising, which became prolific in the late 19th century. The period also saw branded cosmetics rise to prominence, with long-established and well-advertised brands, such as Pears’ Soap, providing one of the few indicators of likely quality and safety. Most cosmetic advertising emphasised the purity and healthfulness of products to distance them from well-known examples of harmful creams, powders, and dyes.

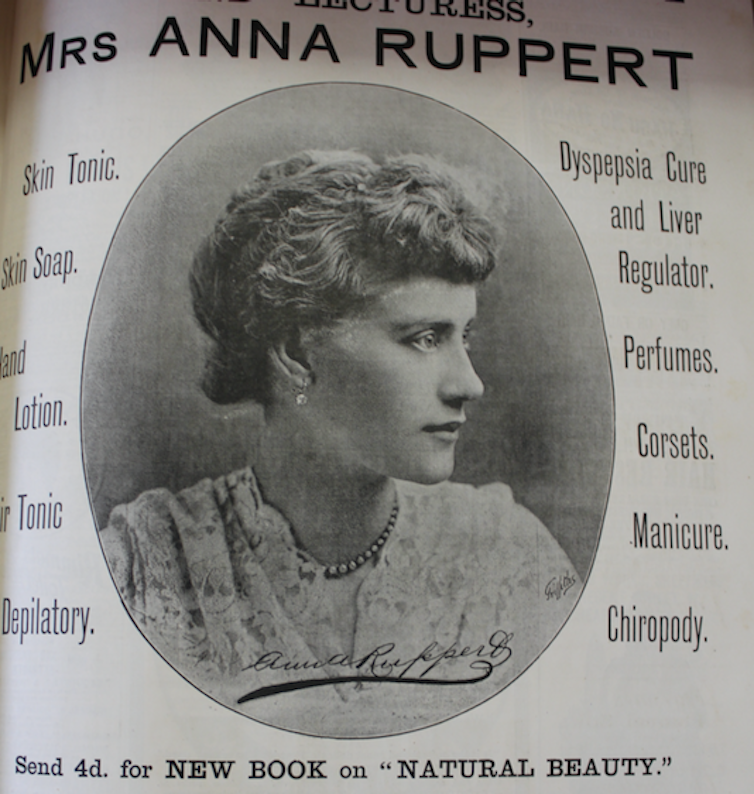

“Celebrated American skin specialist” Anna Ruppert (Shelton) provides a ready example of the spurious nature of some cosmetic advertising and the reality of dangerous tonics marketed as “natural” and therefore healthful in this era. Throughout 1891 and 1892, numerous advertisements appeared in British women’s magazines, including high-quality publications such as The Queen, for lectures to be held in London by a purported American beauty expert.

The ads mentioned Ruppert’s book on “natural beauty”, as well as promoting various products including a skin tonic. Her signature tonic was originally marketed as “Face Bleach” in the United States, tapping into the demand for lighter skin not only from white women, but also African American women. The tonic is described in one Queen advertisement as harmless and invisible: “It is not a cosmetic as it does not show on the face after application”.

However, the reality was that Ruppert’s product was dangerous. After a chemical analysis, the British Medical Journal revealed in 1893 that the skin tonic included the harmful ingredient “corrosive sublimate (bichloride of mercury)”, and it was implicated in the mercury poisoning of a “Mrs K”. As Caroline Rance discovered, that same year, Ruppert was prosecuted for infringing the Irish Pharmacy Act and her reputation was badly tarnished as a result.

Cosmetics originated in homemade preparations, with long traditions of women concocting their own skin remedies. However, the advice and recipes given in beauty manuals were no guarantee of safety. One British “Treatise of the Toilet and Cosmetic Arts” entitled The Practice of Perfumery from 1870 included a recipe for one of the first depilatory creams, poudre subtile. The ingredients call for half an ounce of “sulpheret of arsenic”, although the author does warn that the preparation is “dangerous” and that “utmost caution” should be used.

Warnings such as this one indicate that the harmful effects of certain cosmetic products were well known. Another manual, Beauty: How to Get it and How to Keep It, from 1885 advised readers to avoid hair dyes because they “are sometimes injurious to the health; those that contain lead or mercury are especially so, and have been known to cause serious illness.” This fear of harmful dyes is reflected in the many magazine advertisements of the period for “hair restorers” that promise to return grey hair to its original shade without the use of “dyes”.

Dangerous home-spun beautifying techniques were also the subject of warnings. For instance, Toilet Hints, or, How to Preserve Beauty, and How to Acquire It from 1883 strongly advised women not to toy with the use of Belladonna berries to dilate their pupils. The use of an extract from the berries could cause blurred vision or even permanent blindness with prolonged use. This beauty guide offered up another, less dangerous, method for adding a spark to the eyes:

If your eyes look dull, drink a glass of champagne rather than touch belladonna.

A gendered culture

Disgraced skin specialist Anna Ruppert wrote in her A Book of Beauty in 1892 that a woman could never neglect her appearance, as even “[t]he most noble beauty, if unattended, will soon lose its charm”. Her comment has several important resonances with beauty culture today.

First, it is still primarily women who seek out cosmetics and cosmetic procedures. Ruppert’s advice to the Victorian woman was that maintaining her looks was vital to maintain a happy marriage. Our modern, postfeminist view is that women now make the “choice” to follow beauty and fashion norms.

Second, beauty is still understood as a process of ongoing work and maintenance. Procedures like Botox can be used pre-emptively to ward off wrinkles and sagging, but it requires continuous usage over time to maintain its effects.

Third, and most importantly, the gendering of cosmetic use means that women are most affected by dangerous products and procedures. As Matthews David points out, cosmetics and dyes continue to be less stringently regulated than products like shampoo and deodorant, which fall under the category of “personal care”.

Further reading: Health risks beneath the painted beauty in America’s nail salons

Several centuries of lax attitudes toward the composition of cosmetics and now non-invasive cosmetic procedures add up to not only a collection of macabre or grotesque stories.

From lead-filled Bloom of Youth to cosmetic fillers being delivered under questionable conditions, the history of dangerous cosmetics shows us the harms that women have suffered to meet expectations of what is beautiful.![]()

Michelle Smith, Senior lecturer in Literary Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: