What Americans can learn from Danish masculinity

What Americans can learn from Danish masculinity

When a leader cries in public, is it a sign of weakness?

On Jan. 14, 2023, Denmark’s Crown Prince Frederik was crowned King Frederik X after his mother, Queen Margrethe II, announced she would be abdicating the throne during her annual New Year’s Eve speech.

After the queen signed a declaration of abdication in a private meeting, the king stepped out on the balcony of the Danish parliament – Christiansborg Palace. In front of a throng of 300,000 people, the king waved, teared up and waved again, before wiping away the tears with his white-gloved hand. He later shed more tears as his wife and children joined him on the balcony.

The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Guardian eagerly noted the emotional moment. One Danish newspaper headline simply read, “The King’s Tears,” while a Danish celebrity magazine featured a series of images of the king wiping his eyes.

In much of the world, tears and masculinity don’t mix. Crying can signal vulnerability and weakness, particularly for men in charge. Showing your emotions is viewed as too effeminate.

But in Denmark, the king’s tears didn’t minimize his popularity. In fact, they burnished it: Showing a feminine side is a core part of Danish masculinity.

As a native Dane and a psychologist, I’ve studied Denmark’s unique conception of manhood, which contrasts with masculine ideals in the U.S.

What makes a man?

Different cultures have different expectations for how men should act, look and express themselves.

American men are often expected to be tough, strong and stoic. It’s important that they don’t appear too effeminate.

Research shows that in Denmark it can be acceptable – even desirable – for men to show a feminine side.

In a study on masculinity and manhood in the U.S. and Denmark, my colleagues Sarah DiMuccio and Megan Yost and I found that among young heterosexual men, Danish men were more likely than American men to describe ideal men as being caring, loving, considerate and empathetic, which in the U.S. are usually seen as feminine characteristics.

Many of the young Danish men in our study celebrated these qualities in their male friends, for whom they expressed deep affection. They recounted long phone conversations and hugs. They’d routinely say, “I love you,” or use heart emojis in their text messages.

They didn’t seem too concerned about being seen as too effeminate, because they didn’t see avoiding being girly as part of manhood.

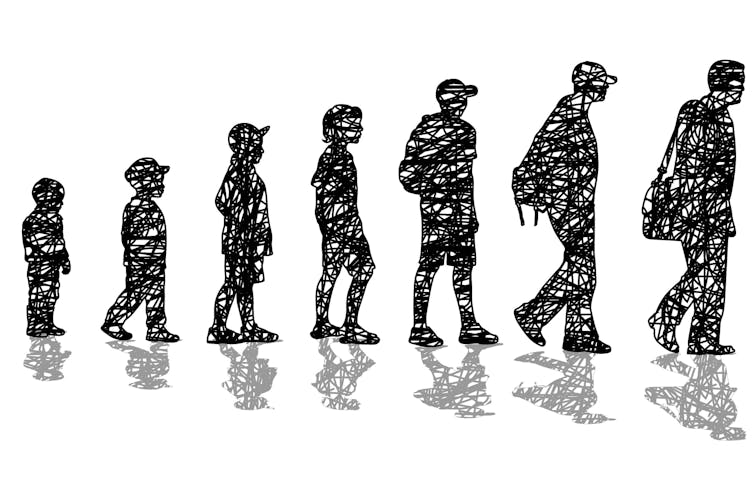

Instead, a number of the Danish participants in our study described manhood in opposition to boyhood. Put simply, you are a man when you are no longer a boy.

This made their manhood seem less precarious: It was seen as purely developmental, rather than something that needed to be constantly reinforced.

In contrast, the American men viewed manhood in contrast to womanhood: You’re a man when you’re not a woman. For example, we asked one participant how his brothers responded if he did something they deemed unmanly.

“By beating (me up) a little bit and calling me a girl,” he replied.

The positioning of manhood against womanhood makes it more precarious: It must continuously be reinforced. To the American men in our study, suppressing any feminine qualities, including showing emotion, was one way for them to make sure others saw them as “man enough.”

In another study examining masculinity among Danish men, the men said that ideal men should have an emotional side; to them, it was a sign of balance and authenticity.

When the men were asked about a public figure or male celebrity who showed the most acceptable masculinity, many of them even mentioned then-Crown Prince Frederik. They saw him as having a good mix of traditionally masculine qualities – he’d served in the military and is athletic – and softer, more feminine qualities: He is considerate of others, talks about his feelings and is engaged with raising his children. He even picks up his children from day care on his cargo bike.

The men in the study added that any good father should be more than a provider. He ought to be present, caring and engaged with his children.

Gender in the land of equality

Why are there such profound differences in conceptions of masculinity between these two Western nations?

It could have something to do with the fact that Denmark has some of the highest ratings of gender equality in the world. For example, in 2021, the U.N. ranked the U.S. 44th in gender equality after assessing health outcomes, political representation and workforce participation among men and women. Denmark, on the other hand, was ranked as the most gender equal country in the world.

In the Danish workplace, employees and employers are on more equal footing. Managers tend to wield a participatory and democratic leadership style that is informal, open and trusting. There’s an emphasis on a good life-work balance.

This leadership style upends traditional notions of masculinity because it focuses on communal values: empathy, collaboration and relationship-building. It contrasts with traditionally masculine leadership, which in psychology is called “agentic leadership,” and which centers on dominance, power and achievement.

The U.S. tends to champion more masculine values and attitudes in the workplace. In one experimental study, American men who cried in response to a negative performance evaluation were judged more harshly than women who cried in the same circumstances, because it violated expectations of appropriate masculine behavior.

Royalty in an egalitarian country such as Denmark might seem odd to some people. But King Frederik X, whose role is more cultural and ceremonial, is simply embodying Danish sensibilities.

At his party, he can cry if he wants to – and he’ll be all the more beloved for it.![]()

Marie Helweg-Larsen, Professor of Psychology, Dickinson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: