Barbie for boys? The gendered tyranny of the toy store

Barbie for boys? The gendered tyranny of the toy store

“I didn’t encourage my daughter to play with Barbie dolls and dress up in flouncy fairy costumes, but she just gravitated toward them.”

When confronted with the idea that gendered marketing and stereotypes have a substantial impact on children’s play, many parents make claims such as this that suggest that girls have an innate predisposition to acquire pink, glittery toys.

Not only do many parents deny that gender stereotypes shape what kinds of toys children feel allowed to play with, but so too does our Prime Minister. On hearing of the No Gender December campaign, which encourages people to consider what kinds of toys they are buying in the lead-up to Christmas, Tony Abbott dismissed it as “political correctness”. We must, he argued, “let boys be boys, let girls be girls”.

No Gender December, and similar campaigns such as Let Toys Be Toys, nevertheless suggest that the gender stereotyping of toys restricts children’s creativity and development. They also argue that the separation of toys for girls and boys contributes to gender inequality by marking off certain pursuits, careers, and tasks as unsuitable for one gender or the other.

Letting children “be” boys or girls implies that there is a natural set of likes and dislikes for each gender that are unaffected by the culture in which we live. Behind this view is the sense that toy preferences are rooted in biology, such that only girls are drawn toward baby dolls because they are driven to nurture, while boys will be attracted toward active toys such as guns.

There are several problems with this viewpoint. First, to take one type of toy as an example, very young boys seem equally attracted to dolls. Cordelia Fine’s Delusions of Gender refers to a study that measures young children’s reactions to dolls, finding that boys only begin to reject dolls around the age at which they can be taught that dolls are intended only for girls.

If we were able to create an environment in which limiting cultural views about gender were not presented to children through the media, advertising, or enforced by their peers or parents, then in all likelihood many boys would continue to show an interest in dolls beyond infancy, as some still do regardless of these factors. That would truly be letting “boys be boys”.

Indeed, such an attempt to counter the effects of gender segregation in toy stores is already in progress in Sweden.

In 2012, Top Toy, the franchise holder for Toys R Us in Sweden, produced a catalogue with a girl shown deftly working a Nerf gun, a small boy cradling a baby doll, and both a boy and girl playing with a doll’s house. International media reports about the catalogue reacted along predictable lines, suggesting that gendered separation of toys mirrored children’s natural preferences and that the concept of gender neutrality was bizarre and artificial.

Nevertheless, Toys R Us Sweden has only continued to move towards gender neutrality in its stores, with the physical layout being transformed such that typically masculine and feminine toys are intermingled throughout the aisles.

Second, these supposedly “natural” preferences for particular kinds of toys or colours shift according to what our culture believes appropriate for children and what the toy industry finds profitable.

We know, for example, that the “pinkification” of girls’ toys is a relatively recent phenomenon, in part motivated by a desire to improve sales by rendering the most innocuous of toys unusable by siblings of different sexes.

Similarly, where Lego was once imagined as a relatively unisex toy that encouraged creativity and developed fine motor skills, in recent years a separate line intended for girls, which involves less freedom to construct, has become a bestseller.

We place great strength in the idea that the kinds of toys that children play with helps to determine the kind of adults they will become, especially in terms of how appropriately masculine or feminine they will be. Even children know enough to act as “gender police” if a boy or girl attempts to play with a toy outside the accepted items for his or her gender.

The No Gender December campaign notes that:

It’s 2014 – women mow lawns and men push prams but while we’ve moved on, many toy companies haven’t.

Yet some of the main markers of gender inequality refuse to budge in countries including Australia. The majority of housework and childcare is still performed by women, even as more women are in paid employment than ever before. High-paying industries and senior positions within most fields remain dominated by male employees, while feminised occupations, involving caring or working with children, remain low paying.

The segregation of toy aisles is a reflection of a society in which gender inequality is normalised and children are taught to understand that the disparity between male and female social roles is inescapably natural.

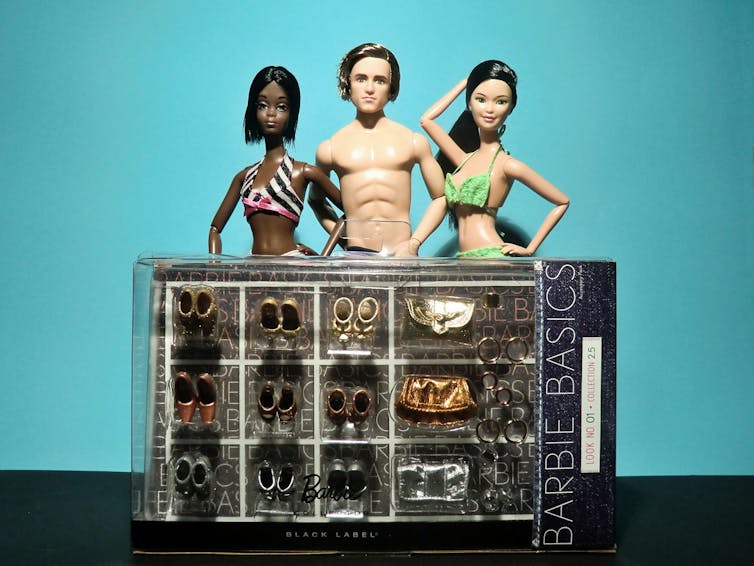

While making it easier for girls who want to romp adventurously to do so and for boys who want to show an interest in clothing to play with Barbie won’t single-handedly correct gender inequality, it will help to minimise the internalising of gendered limitations during childhood. It also won’t stop girls being girls or boys being boys.

See also:

Leave Barbie alone – so we can talk about how kids actually play![]()

Michelle Smith, Research Fellow, Centre for Memory, Imagination and Invention, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: