Bias be gone! Can our unconscious prejudices be overcome?

Bias be gone! Can our unconscious prejudices be overcome?

Bias comes in more flavours than Baskin-Robbins ice cream. Well known biases of gender, race, age, class, weight, and media barely scratch the surface.

Psychologists catalogue numerous biases of hindsight and foresight, attention and memory, reasoning and intuition, as well as a litany of mental illusions, fallacies, neglects, gaps and aversions. There is even the bias blindspot – our mistaken belief we are less biased than others – and the “bias bias”: the tendency to use the concept of bias too freely.

Review: The End of Bias: How We Change Our Minds - Jessica Nordell (Granta)

Behind this proliferation of biases is the fundamental insight that human thinking is fallible. We fall prey to a range of errors that pull and push us away from the ideals of rationality and fairness. If our departures from good thinking and right action stem from these biases and errors, then identifying and remedying them is an urgent task.

Jessica Nordell’s The End of Bias is a powerful expression of the view that bias is at the root of many social divisions and inequalities. Rather than simply making this diagnosis, Nordell presents a strong case that bias can be uprooted. Her book is a bracing review of the state of the science of bias, and especially how its lessons can be applied to promote progressive social change.

Nordell begins her tour de force with an examination of the modern social psychology of prejudice.

Recognising that racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice persist, despite declines in overt bigotry, psychologists have come to the view that many social biases are automatic, unconscious, or habitual. We can sincerely proclaim our commitment to egalitarian values, but still discriminate in our actions and reactions.

The early chapters of The End of Bias explore the psychology of these forms of discrimination, introducing the reader to recent understandings of stereotyping, priming (the automatic triggering of mental associations), and cognition outside awareness. Nordell shows how discrimination can be subtle in nature, but powerful in effect. Its thousand cuts compound over time.

Unacknowledged biases can lead doctors to withhold pain medications from groups stereotyped as overly emotional or unfeeling, one recent study finding that some white medical trainees believe Black people have literally thicker skin than Whites. In the medical context, it can also lead to missed diagnoses and harsh or dismissive treatment decisions.

Unconscious biases can lead police officers to overestimate the physical threat posed by Black suspects and to mistakenly perceive weapons and hostile intent, often with tragic consequences.

Nordell argues that biases in school settings underlie failures to identify minority students as gifted and the unequal use of discipline. Related biases obstruct the hiring of under-represented groups in universities and other organisations, and restrict their progression up the professional ladder.

Changing hearts and minds

The End of Bias starts with psychology, but it doesn’t neglect the systemic, institutional, and cultural dimensions of discrimination and inequality. Nordell neither reduces bias down to the individual, nor up to social structure.

She recognises how mental biases and societal practices are mutually reinforcing. Enduring inequalities won’t crumble under the force of a few diversity seminars, but neither will top-down solutions work without changes in hearts and minds.

This stereoscopic focus on individual thinking and broader social systems is clearest in Nordell’s explorations of how bias can be overcome. Her emphasis throughout the book is on real world interventions that work. These programs range from workshops that target individuals, to inter-group contact experiences, such as jigsaw classrooms and integrated sporting contests, to shifts in institutional processes and social norms.

Among the de-biasing interventions Nordell examines are genderless pre-school education, mindfulness training for police officers, role modelling for women in STEM disciplines, and community policing initiatives.

Change can be made by simple tweaks and nudges, but also by wholesale transformations of organisational culture. The repertoire of promising interventions is large and growing, although Nordell acknowledges that the evidence for their efficacy is often limited and some interventions can backfire.

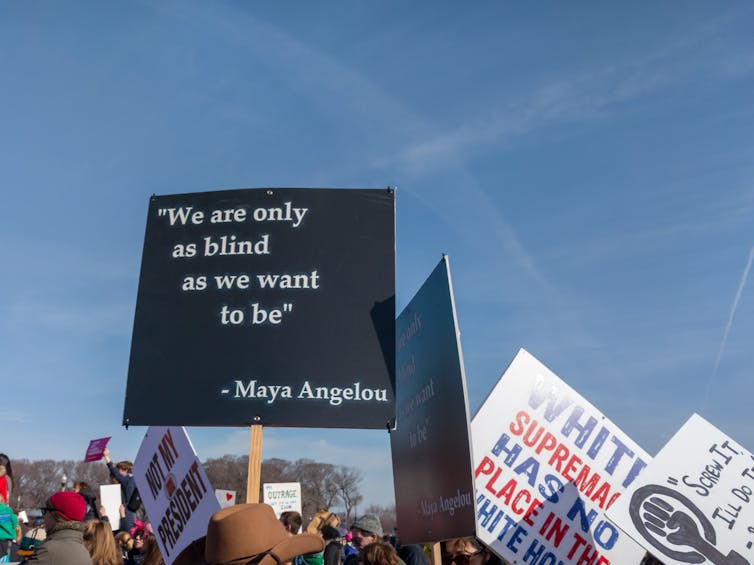

She underscores how consciousness raising is rarely sufficient: if bias is often habitual and automatic, mere awareness and good intentions will not overcome it. Similarly, although our tendency to view one another through the distorting lens of group stereotypes might tempt us to de-emphasise social categories, Nordell argues that this is not a desirable option. Colourblindness is not a realistic aspiration in a world where race matters.

Limitations

The scope of The End of Bias is international. Nordell’s case studies come from Kosovo, Rwanda and Sweden. But her main point of reference is the USA, and its racial divides in particular. The book explicitly addresses an American audience, though much of its message translates into other contexts.

Nordell’s case for overcoming bias is passionate and frequently persuasive, but it is has its limitations. At times, she overstates the firmness of the evidence on which the science of bias is built.

For example, strong early claims about the predictive power of measures of unconscious bias have faced serious challenges. How we should interpret the meaning of such apparent biases is also under a cloud. Should they be treated as signs of a person’s automatic prejudice or merely as evidence of their exposure to an unequal society?

Similarly, Nordell’s references to “stereotype threat” – people’s impaired performance when they fear they will be judged negatively based on a group stereotype – overlook substantial challenges to the robustness of the phenomenon.

The concept of microaggression, a term coined to describe implicit or unconscious forms of discriminatory behaviour, is explored uncritically, without acknowledging how problematic its definition and use have become, or whether it is a helpful way to understand the undoubted reality of subtle bias.

More generally, we might question whether bias is a sufficiently solid concept to bear the explanatory weight Nordell places on it. What counts as a bias is never defined. It functions as an all-purpose idea that can stretch to cover almost any social phenomenon.

Indeed, bias has several weaknesses as an account of social inequalities. It implies that biases are grounded in irrationality, when they often reflect real differences in interests, values, and material resources. Such differences cannot be reduced to the mental errors of one side. As work on the “bias bias” reveals, what can superficially appear to be a cognitive error often is not.

Nordell occasionally takes the “bias bias” to extremes. She pictures biases as comprehensive breaks with reality, sometimes describing them in psychiatric terms. She refers to “White psychosis” and writes that “There is, in the privileged mind, ongoing delusion”. Biased individuals, according to Nordell, “do not see a person. They see a person-shaped daydream.”

This view of bias as blindness, madness, fantasy and delusion – not to mention the suggestion that it is confined to some groups or individuals – is an extreme departure from the psychology of bias with which the book begins.

Bias has additional problems as a sovereign concept for understanding social injustice. As systematic tendencies and patterns that appear in the aggregate, biases are often very hard to identify as the causes of specific events, just as it is challenging to identify a known risk factor for a disease as the cause of a particular person’s case. Attributing specific events and outcomes to bias is often done too quickly and confidently. Other factors may be at play.

Biases are usually vulnerable to alternative explanations and confounding factors. There is ongoing debate about the extent to which some race-related biases are at least partially explained by socioeconomic class. Similarly, a significant proportion of the gender wage gap reflects motherhood penalties rather than gender itself.

If these alternative explanations have merit, then some supposed race and gender biases may not be, in fact, primarily about race and gender at all. Such uncertainty about whether apparent biases might be explained by other factors is a significant problem for the bias-first perspective.

The End of Bias makes its case with passion and moral force. At times, its intensity is expressed with an all but religious zeal that may seem foreign to Australian ears. The path to ridding oneself of bias is presented almost as a spiritual quest or conversion, complete with confessions, revelations and purifications.

The historical origins of contemporary American inequalities are described as indelible original sins.

“Perhaps ‘White fragility’ or ‘male fragility’,” Nordell writes, “… is actually a felt connection to an old moral injury, one that could even have been committed by one’s forebears.”

Combined with its polarised analysis of bias as the psychosis of the unenlightened, reminiscent of a world of angels and demons, The End of Bias seems coloured by American religiosity.

It remains a powerful book, regardless. Nordell paints an optimistic picture of our growing capacity to reduce bias. She offers a valuable and lucid introduction to the social psychology of prejudice. Some readers will have their commitment to the fight against bias strengthened, others may baulk at how that fight is framed, but all will be educated.![]()

Nick Haslam, Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: