Bathrooms are political: how gender-inclusive toilets can combat indignity and violence

Bathrooms are political: how gender-inclusive toilets can combat indignity and violence

A new hate crimes bill is inching closer to the possibility of becoming law in South Africa. The bill entrenches human dignity as a foundational value of the country by providing for penalties for explicit acts of violence and discrimination motivated by prejudice and intolerance.

However, prejudice and intolerance can also be expressed and experienced in everyday ways that are often taken for granted. The bill does not necessarily acknowledge this. It’s crucial to acknowledge that acts of discrimination happen not only in obvious forms of hate speech and violence in public spaces. They also happen in the everyday private spaces that form part of our homes, faith spaces, workplaces and, in particular, the bathrooms available in these spaces.

As psychologists and scholars working in the fields of sexualities and gender in a country with high levels of gender-based violence, we are sensitive to the anxieties of all people and, in particular, women, who voice an almost omnipresent sense of the threat of violence in public spaces. But we’ve also come to understand that people whose gender appearance may be “non-normative” often feel unsafe in public bathrooms.

As the debate around gender-inclusive toilets rages around the world, we argue that shared bathrooms create more inclusive societies that ultimately protect human dignity.

Bathrooms are public-private spaces

The bathroom, a seemingly private yet inherently public space, has become subject to intense scrutiny. Especially regarding the rights of trans and gender diverse individuals, both in South Africa and abroad. (A transgender person identifies with a gender different from that of their sex that’s assigned at birth. A gender diverse person has a gender identity or expression that’s at odds with what’s perceived as being the social norm.)

The public bathroom has become a lightning rod for a general social anxiety about safety and gender. Are women safe if a trans woman uses the same bathroom? What does it mean to the gender (and indeed sexuality) of men if a trans man uses the “men’s bathroom”? Aren’t children at risk if anyone can “decide” they are trans and walk into a public bathroom? Why can’t we keep things simple and make people go to the bathroom according to their sex assigned at birth?

It’s in this context of moral and personal panic, we argue, that in fact it’s trans and gender diverse people who are most at risk of a “quiet violence” as they attempt to access and navigate these everyday spaces.

This discrimination is “quiet” because it does not appear as the kind of overt act of violence that the hate crimes bill seeks to legislate against, such as a transphobic slur or assault. However, it remains a form of violence because trans and gender diverse people feel policed and threatened navigating these spaces.

Bathrooms as political arenas

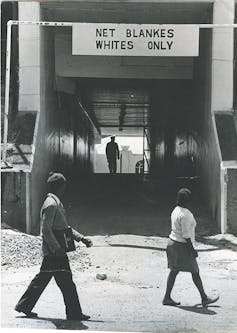

Bathrooms hold more than a functional purpose; they’re historically significant sites of overt and covert political struggles. Throughout social justice movements worldwide, bathrooms have played pivotal roles. In the US, bathrooms became contested spaces during civil rights movements for women’s rights, desegregation and disability rights.

Apartheid also enforced strict policing and segregation of public amenities including swimming pools, beaches and toilets. This perpetuated institutionalised racism and a disregard for the dignity and worth of people of colour.

This legacy endures in historically marginalised communities, where the “bucket system” (non-flush toilets where a bucket is used to collect waste), pit latrines and inadequate sanitation facilities persist.

The gendered nature of bathrooms

Choosing between “men’s” and “women’s” bathrooms subjects an individual to a normative system that organises and disciplines their body based on a sex-segregated understanding of gender.

This system enforces a binary of gender, defined solely by two biological sexes – male and female. For trans and gender diverse individuals, selecting a bathroom becomes a calculation of self-preservation. This requires self-surveillance in an effort to minimise the likelihood of harassment and violence for deviating from normative gender presentations.

Violence and discrimination in bathrooms

Bathrooms are often reported to be distressing spaces for trans and gender diverse individuals, becoming sites where they experience discrimination and exclusion. Occupying gendered facilities can lead to discomfort, verbal abuse and physical assault. Being forced to “hold in” basic biological functions can also result in health problems.

Calls for these individuals to use bathrooms aligned with their assigned sex at birth don’t only demonstrate the binary model of gender. They are discriminatory and foster conditions that perpetuate violence, confusion and negative attitudes towards trans individuals. It’s crucial to recognise that violence against trans and gender diverse people is often overlooked.

Ensuring recognition and safety

It’s critical to acknowledge women’s concerns regarding the prospect of sexual assault in using gender-inclusive bathrooms. It’s equally crucial to challenge the notion that bodies assigned male at birth are inherently violent and that safety can only be guaranteed through gender-specific or sex-segregated bathroom arrangements.

Studies from Australia, the US and the UK have suggested that gender-inclusive facilities do not compromise safety or privacy.

In fact, they serve as catalysts for social change, challenging binary constructs and debunking the notion of inherent male violence. Reducing violence to a specifically gendered body overlooks the complex social psychology of violence, which is rooted in gendered power asymmetries, control and dehumanisation.

By recognising the discrimination that trans and gender diverse people face in these spaces and implementing new gender-inclusive bathroom arrangements which accommodate all people, we believe that inclusive societies can challenge harmful assumptions and contribute to the cause of dignity for all.

This article was revised.![]()

Jarred H Martin, Senior Lecturer in Clinical Psychology, University of Pretoria and Pierre Waldemar Brouard, Acting director of the Centre for Sexualities, AIDS & Gender, University of Pretoria, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: