The truth about Madonna’s hairy armpits and sexy older women

The truth about Madonna’s hairy armpits and sexy older women

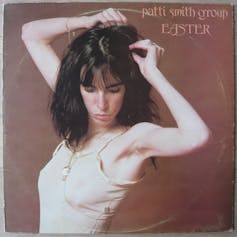

In 1978, the cover of Patti Smith’s album Easter was sufficiently shocking and mystifying to many people that some US record stores, especially in the south, according to Smith, refused to display it. While the album did contain a song with a racial slur in the title, what was most immediately confronting was that the pose Smith adopted on the cover unselfconsciously displayed a thatch of underarm hair.

Some 36 years later and a selfie posted by Madonna on Instagram, in which she adopts a similar pose to reveal a more stage-managed growth of hair, has prompted a profusion of media articles and tens of thousands of comments, many of which express repulsion. Madonna used the hashtags #artforfreedom, #rebelheart and #revolutionoflove, which indicate that she was presenting the photo, in which she wears a significant amount of make-up and a bra, as subversive.

Why is a celebrity’s calculated and seemingly temporary decision not to shave significant enough for this many people to express an opinion about it? And is the response solely about beauty expectations relating to body hair? Or is it also grounded in ubiquitous ageism towards women over 40 who dare to highlight their sexuality?

Certainly it’s possible to argue that the media buzz about Madonna’s underarm is symbolic of just how vapid and celebrity-obsessed we have become. Yet the responses to the image reveal much about cultural attitudes towards women and the continued force of expectations about their appearance and behaviour.

In the 1970s, second-wave feminism flourished. It challenged female beauty norms, such as shaved legs and underarms and the wearing of make-up. Smith’s Easter album cover, with the singer bare-faced and dressed in a plain singlet, is an apt reflection of an era in which some women sought to free themselves from the time and cost demanded by beauty regimens.

In the decades since, ideas about beauty culture have shifted dramatically. Postfeminism embraces the notions of individual choice, agency, and empowerment. As such, conforming to Western standards of beauty and sexiness need not be understood as a sign of women’s oppression.

In addition, consumer culture has ramped up attempts to police and regulate women’s bodies. Dove’s “beautiful underarms” deodorant campaign, for example, attempts to create a new site of concern and embarrassment for women. Not only must women’s underarms be hairless, but the imperfections caused by shaving must be smoothed out by a new product in order to make them “prettier”.

Madonna had already posed in a series of nude modelling shots with long, untrimmed underarm and pubic hair in 1985. Whether she intended for the hair to look sexy, was aiming to be controversial, or had no particular motivation for leaving the hair as nature produced it, is not clear.

What is evident, however, is that these youthful shots do not inspire the same degree of animosity and disgust as her new Instagram photo. The profusion of comments at Instagram and in response to articles usually connect the disgust with the fact that Madonna is 55-years old.

She is repeatedly called “a hag”, “elderly”, and her body is described as unattractively “wrinkled”, though only light creasing is visible around her eyes. Because she posed in a bra, with her ample cleavage displayed, Madonna has become a target for cultural revulsion surrounding women who are no longer young, but still wish to be viewed as sexually attractive.

The implication in much of this discussion, and in the heteronormative obsession with the sex appeal of girls and young women, is that men do not generally wish to see the bodies of women over the age of 40, and especially not over 50. While we are all indeed at our physical peak in our younger years, the emphasis on women’s sexual attractiveness being dependent on their youth, and often childlessness, is disproportionate.

It is now ten years since Janet Jackson’s intentional “wardrobe malfunction”, in which she exposed her nipple during a performance at the Superbowl. Comedian Chris Rock crudely joked at the time:

You can’t just whip out a 40-year-old titty, that’s your man’s titty. 20-year-old titty, community titty. That’s for all to see.

Despite the problematic assumptions in his humour, Rock is correct that young women’s bodies are seen as community property to be viewed and admired, but older women’s bodies are not supposed to be displayed “for all to see”. Jackson’s bared breast became a joke.

She was accused, like Madonna, of a kind of sad desperation in attempting to flaunt her body when she was past her prime. Madonna is a skillful manipulator of her image. She has miraculously maintained a pop music career across four decades in a way that has proven impossible for any other female artist.

But even a force as formidable as Madonna is no match for the renewed pressure on women to conform to narrow beauty ideals and cultural demands for women to become increasingly invisible as they age. ![]()

Michelle Smith, Research Fellow, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Không có nhận xét nào: